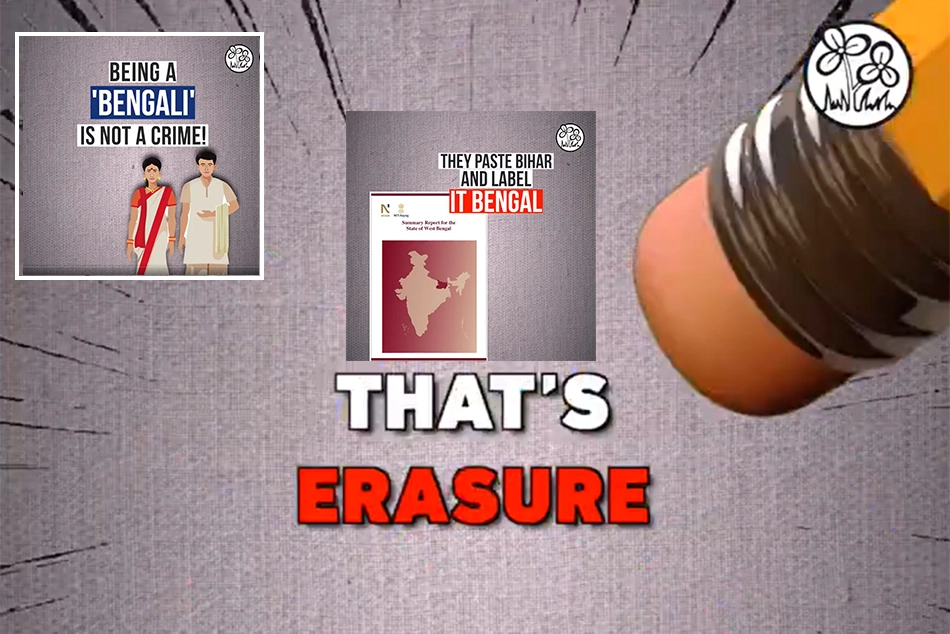

The Othering of Bengalis

Is this erosion of Bengalis presence in India’s mainstream a mere social accident or the result of a well-calibrated political strategy?

For generations, countless Bengalis – especially those from Assam, Tripura and the entire Northeast along with Orissa, Bihar, UP, Rajasthan, Delhi, MP – have grown up bearing the weight of labels such as: “Unwanted”, “Foreigners”, “Bangladeshi”, “Outsiders”, etc. These words have not merely been thrown as casual insults. They have been etched into official narratives, societal mindsets and political discourses. Over time, such stigmatization has inflicted deep psychological scars, eroding a community’s confidence, cultural pride and sense of belonging within their own homeland.

The Partition of 1947 and later the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, unleased demographic, political and cultural upheavals. For Bengalis in India, these events not only reshaped geographical borders but also forged invisible walls of suspicion and prejudice. Entire generations were uprooted – crossing borders with nothing but memories – only to be told that they were “guests” in their own land. This sense of perpetual displacement has remained an undercurrent in Bengalis identity ever since.

Psychological Impact : A Medical Perspective

From a clinical standpoint, the long-term exposure to stigma and exclusion have led to chronic stress, anxiety disorders, depression and generation trauma. Studies in social psychology shows that children who grow up under sustained socio-political alienation often suffer from impaired self-esteem, weakened civic engagement and a heightened sense of vulnerability.

In many Bengali families of the Northeast, young people learn early to conceal their identity or soften their accent to “pass” in a non-Bengali environment – an act of linguistic self-erasure driven by fear of discrimination. Over decades, such survival mechanisms morph into a collective psychological withdrawal, slowly robbing the community of its ability to assert itself in public discourse.

The National Mental Health Survey (2016) revealed that states with high linguistic discrimination reported 25 -30 % higher rates of anxiety and depression among minority language groups. While the report does not explicitly name Bengalis, field studies in Assam and North Tripura do.

A Calculated Marginalization?

The question must be asked: Is this erosion of Bengalis presence in India’s mainstream a mere social accident or the result of a well-calibrated political strategy?

Evidence suggests the later.

Across multiple states, electoral politics has thrived on portraying Bengalis – especially those from the border states, as “suspect citizens.” By weaponizing the refugee narrative and conflating linguistic identity with cross-border migration, political forces have systematically pushed Bengalis away from “decision making” groups – whether in politics, civil administration, academia or corporate leadership.

This is not simply about representation, it is about influence. By ensuring that Bengalis are underrepresented in policymaking, their collective voice is muted, their grievances diluted and their ability to shape their own socio-political destiny is crippled.

From Daily Life to National Politics: The Exclusion Spectrum

Marginalization operates at multiple levels:

- Politics: Few Bengalis from the Northeast or migrant Bengali communities hold significant positions in state or central power structure.

- Bureaucracy: Competitive examinations reveal disproportionately low Bengali representation in IAS, IPS and IFS cadres compared to their population share.

- Economy: In regions where Bengalis form a substantial workforce, they are often excluded from local economic boards, cooperative societies and business associations.

- Culture: Subtle but persistent cultural policy discourages public expression of Bengali heritage – whether in literature, festivals or language use.

A Positive Way Forward: Role of Government and other Linguistic Communities

Healing this fracture requires more than token gestures.

- Government Action: Enforce anti-discrimination safeguards to protect linguistic minorities not only in pen and paper but in practice. Enforce a proportional representation of Bengalis in administrative and political roles. Recognize Refugee Histories (including the Bengalis) in school curricula to foster empathy.

- Civil Society & Other Linguistic Communities: Promote inter-community cultural exchanges that go beyond token celebrations. Dismantle stereotypes by engaging in collaborative media, art and academic projects. Encourage education that normalizes linguistic diversity.

Conclusion: From Alienation to Reclamation

Bengalis in India do not seek privilege – they seek parity. They do not want to dominate – they want to belong. The stigma of being perpetual outsiders has gone on for too long, breeding silent despair and disengagement. Unless India addresses this marginalization head on – through representation, respect, love and recognition, the country risks losing one of its richest cultural streams to the slow death of alienation.

The choice before us is stark: Allow a community’s identity to fade into reluctant assimilation or ensure that it thrives as an integral part of the Indian mosaic. For, when people lose their place in their own homeland, the loss is not just theirs – it is the nation’s.

[The writer, Bidhayak Das Purkayastha, is a self-employed Engineer from Assam with a deep passion for writing. He authors articles, columns and poems in both English and Bengali, focussing primarily on socio-political issues. Committed to social causes, he actively works for the welfare of suppressed and oppressed communities, using both his professional skills and his writing to advocate for justice and equality.]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic